Classic Reissue: How to Sell the Greatest Actor of All Time

Daniel Day-Lewis worked hard to be The Greatest, and he wasn’t above a fawning profile or two.

We’re heading into another Oscars ceremony soon, so for our latest classic reissue, it seemed apt to revisit this piece (this one is also free to all subscribers to celebrate the Gossip Reading Club reaching 2,000 subscribers, yay!)

Awards season is dependent on taking this often-ephemeral concept and making it an easily digestible brand to an industry that has long fetishized it. Of course, being good at your job isn’t enough to win you that little gold man. We see this in practice every year with the acting categories in particular. Who has the best narrative? In 2022, we saw the comeback narratives of Ke Huy Quan and Brendan Fraser, the transformative processes of Fraser and Austin Butler, and the biopic cycle fascination with Butler and Ana de Armas. We spent a long time hearing that Elvis accent and leering fascination with fatsuits. All that was missing was some pseudo-Method nonsense and we would have won the Oscar season bingo.

It’s hard to win an Oscar without campaigning hard for it. Sometimes, it happens, as with Mark Rylance and Mo’nique, although the latter faced heavy pushback from colleagues and was reportedly blacklisted as a result. Then again, even the act of not campaigning is, in and of itself, a kind of campaign tactic. Nobody is exempt. Even actors who have expressed discomfort with these expectations gave in when that statuette was in sight (hello, Gary Oldman, Joaquin Phoenix, and many others.) You can be The Greatest Actor of All Time playing a historical legend, but that doesn’t mean you get to sit out the interviews, the round-tables, or all of the self-promotional tedium. Step forward Daniel Day-Lewis.

Time. “Daniel Day-Lewis: How the Greatest Living Actor Became Lincoln.” October 25, 2012. Jessica Winter.

(Image via Time.com)

I remember reading on a film-related forum a while back that Daniel Day-Lewis, the legendary three-time Oscar winner who is widely considered to be one of the greatest actors ever, wasn’t one for the narcissism of the awards campaigning process. My response was to laugh because, oh honey, this dude worked hard to maintain that image. Sure, he famously takes years off between projects and avoids the limelight during those hiatuses, but don’t mistake that for reclusiveness or an allergy to the Hollywood process. You don’t get to be known as a genius without greasing the wheels for yourself.

From the moment it was announced that Daniel Day-Lewis would be playing Abraham Lincoln in a film directed by Steven Spielberg, everyone knew he was winning that Oscar. It didn’t matter who the competition would end up being or the actual quality of the film, we knew that his name would be engraved on the award. “Oscar bait” didn’t even begin to cover the magnitude of this moment. Of course, Lincoln still needed to be sold to the world, as did Day-Lewis himself. He doesn’t do a ton of interviews, so the ones he did do needed to be big. Oprah big, as he’d done with Nine. But since her talk show had ended by this point, Time Magazine, in all of its decades-long prestige, would do.

(I mean, he is amazing in Lincoln.)

The casting of Day-Lewis as Lincoln is positioned here as close to an act of fate. Lincoln's screenwriter Tony Kushner met the actor in his Dublin home and snapped a photograph of him where "silhouette of Daniel against the window—you would absolutely think you were looking at young Abe Lincoln." He certainly looks the part in the film, but even in the Time photoshoot, a deeply classy black-and-white affair that screams seriousness, you can sense the weightiness of his presence. You can’t imagine older DDL doing the Vanity Fair Hollywood Issue or that weird Brad Pitt corpse shoot. The actor’s charm and humility are emphasized, with him saying he wasn’t sure it was “possible to breathe life into Abraham Lincoln.” Even as the fervour of his performances is described, the man himself is depicted as "bit shy and soft-spoken -- endearingly so -- but warm and affable and exquisitely courteous." This profile is about contrasts: the mythic nature of Daniel Day-Lewis the actor, and the near-cozy reality of him as a mere mortal.

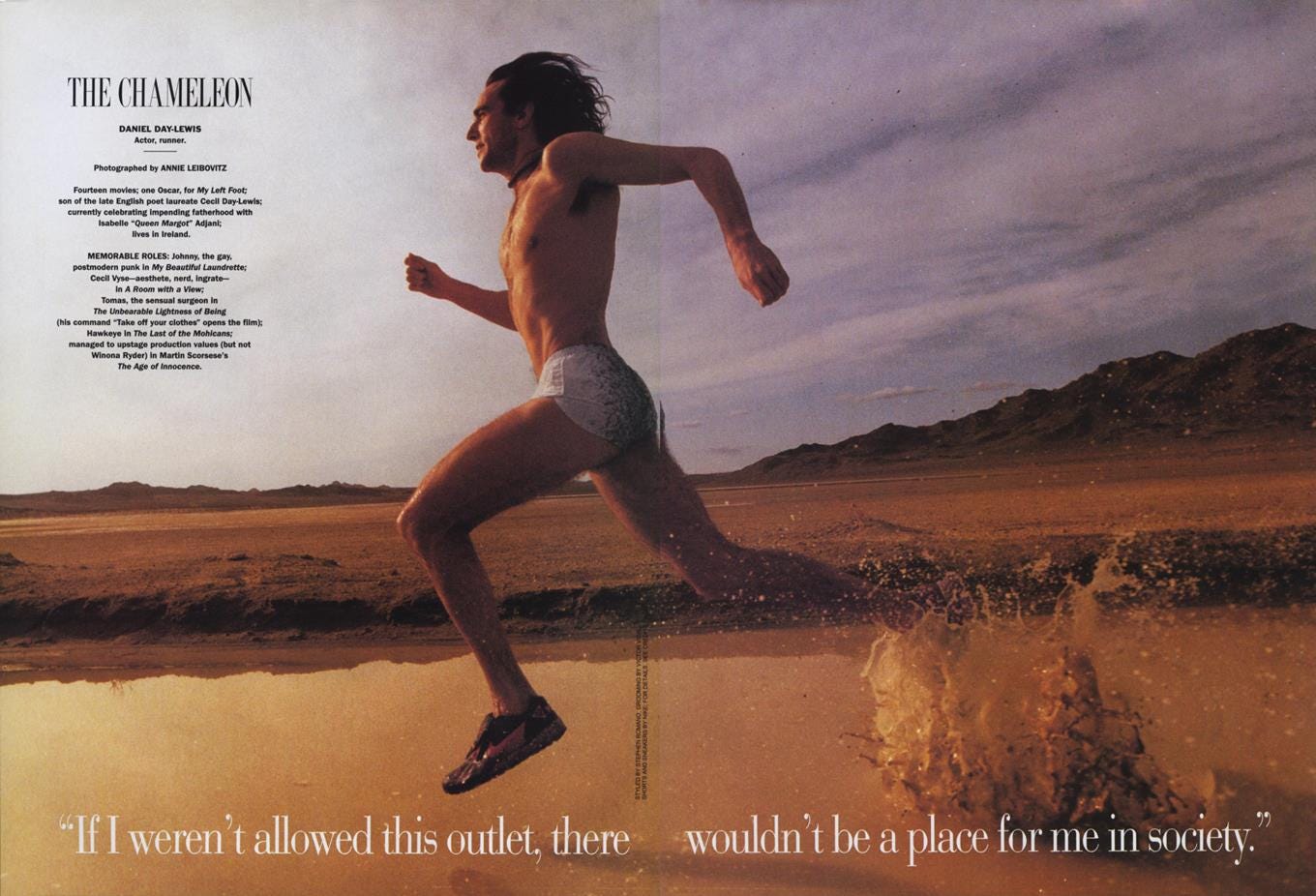

(Remember when DDL was mostly sold as a total smoke show? I won’t forget. Image via Vanity Fair’s 1995 Hollywood Issue.)

It's impossible to talk about Daniel Day-Lewis without getting into the weeds of his method. Time describes it as being “given over to legend” in the same way that Lincoln himself was. What he does is often confused for method acting, which is a specific process pioneered by Stanislavsky and Strasberg wherein actors tap into their own emotions and personal histories to bring realism to their performance. The method in its purest form does not demand that actors stay in character for weeks, even months at a time, yet Day-Lewis’s utmost commitment to his particular brand of acting redefined the method for new generations. This is partly why the level of genius is so thoroughly attached to him: when you’ve entirely changed what people think acting is, how can it not leave an impression?

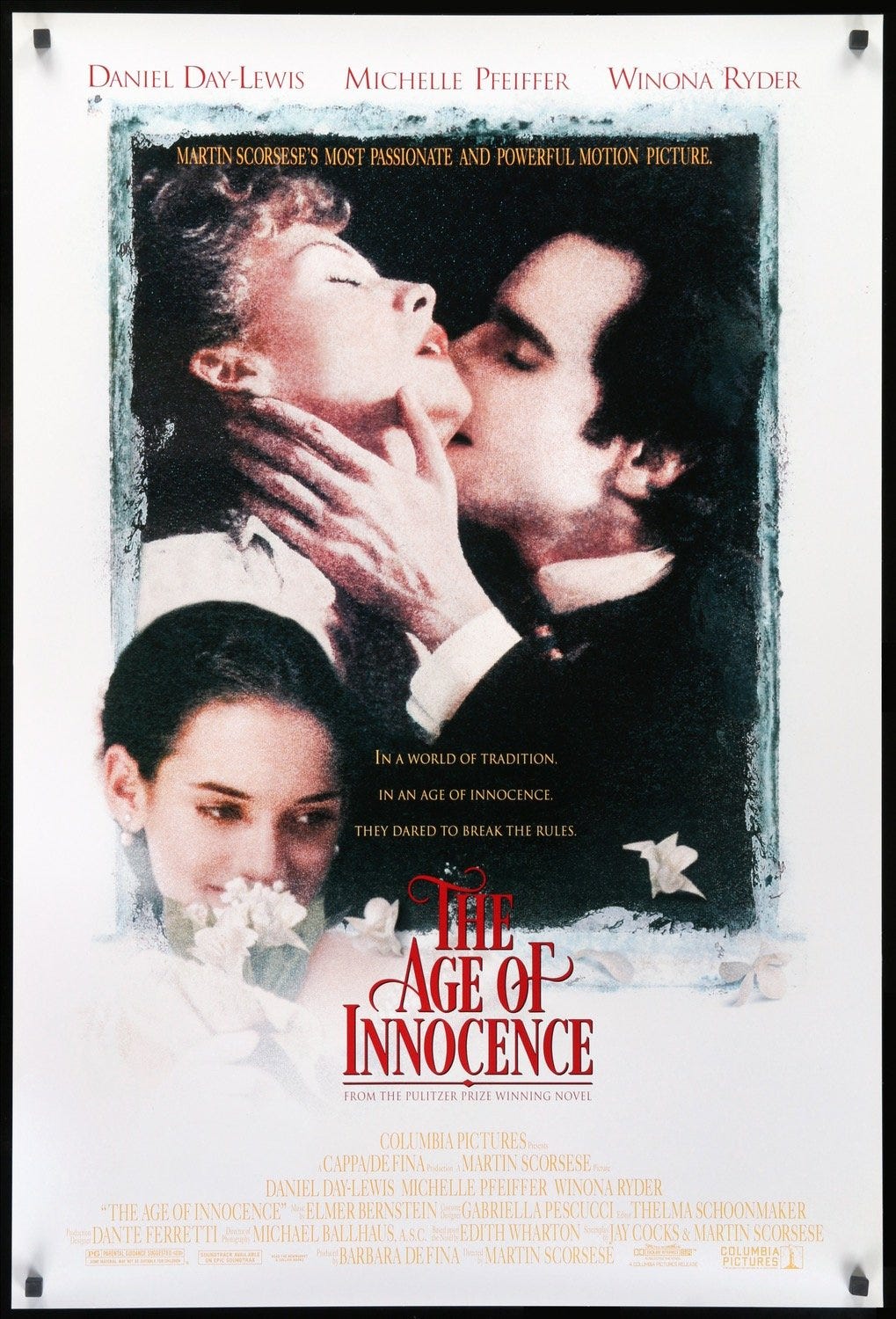

We could be here for hours describing the myriad ways he’s over-prepared for roles: staying in a wheelchair and being spoon-fed by crew members while playing Christy Brown in My Left Foot; living on prison rations and asking the director to hurl abuse at him for In the Name of the Father; training to be a boxer for The Boxer and becoming so good that former world champion Barry McGuigan said he could go pro. It’s not simply that he commits; it’s that he spends years in passionate preparation, going above and beyond learning the accents and so on. The results certainly speak for themselves, although I must admit that I prefer him without all the bells and whistles, such as in his underrated work in The Age of Innocence and the always-underrated The Unbearable Lightness of Being. But in an industry where the most acting is typically equated with the best acting, Day-Lewis set the new standard.

(I own this poster. Best Scorsese movie.)

So, of course, his intensity and extensive techniques are centered here. What made Lincoln so interesting is the bind of playing this icon. Everyone thinks they know what Abe Lincoln looked, sounded, and acted like, but we have no verifiable proof of most of this. Our expectations are rooted in impressions and impersonations, and Day-Lewis had to subvert that without straying into parody. So, Day-Lewis returned to first-person reports to nail the "gentle tenor, reedy and slightly cracked" voice, not the baritone of portentousness we hear at Disneyland. The profile makes sure to emphasize his skill with accents and how he "alone seems capable of remolding his larynx and vocal cords." He’s beyond talented, per Time. He’s almost inhumanely so.

What is most curious about the way this is all framed is that it’s not Day-Lewis himself discussing it. He famously shies away from talking about his methods, remaining self-deprecating about his own abilities and preferring to let the work do the talking. That’s not uncommon for actors of his ilk. Joaquin Phoenix also fits this mould, as does Christian Bale. That makes it tough when it’s your job to talk about yourself, although Day-Lewis is bolstered by a number of high-profile colleagues talking in his place.

Time, obviously, doesn’t want to position any of Day-Lewis’s work or methods as silly, not when they’ve put that Greatest Actor line on the cover. Indeed, there’s a quaintness to their tone at times, such as in describing how he would text co-star Sally Field in character as Lincoln. It makes his work seem approachable, almost, certainly more so here than with My Left Foot or Gangs of New York. It’s not demystified, necessarily. We still get testimonies from former co-stars like Emily Watson, who details how gruelling it can be to work with this method. But it’s all for the greater good, as Watson and Paul Dano praise the process and how it benefitted themselves as well as the final product.

His Lincoln co-star Jared Harris (who is one of my favourite actors) is effusive in his praise and blunt about why Day-Lewis’s methods work. He emphasizes that what he does is what most actors do, just a bit more committed, saying, "His attention to detail and commitment is truly impressive, but people refer to it as being an imposition or intimidating. It isn’t. Actors do that stuff all the time. He just likes to stay in it, and he asks that you respect that by not talking about bullsh*t." It certainly reads as genuine. You don’t imagine them saying this through gritted teeth like Jared Leto’s poor Suicide Squad co-stars. There’s the crucial message here: the Greatest Actor of All Time is also a nice dude.

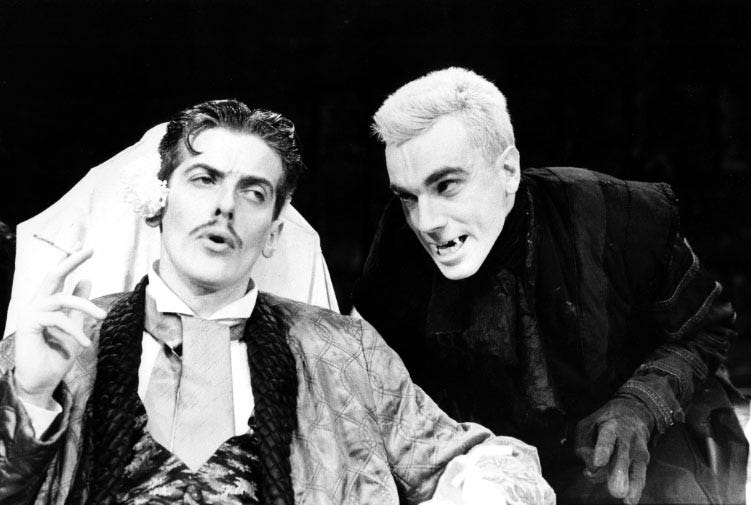

(That time Daniel Day-Lewis played Dracula on-stage. Yes, that is Peter Capaldi.)

I’m sure this is all part of the selling of Day-Lewis and Lincoln, this all-encompassing message of greatness and gentlemanly gratitude. I try not to get too jaded with this newsletter on such matters. While reading this profile, I thought about the stories of “method acting gone too far” that followed Lincoln, and the ways such crushing self-flagellation were positioned as acts of artistic worthiness. Think of Leonardo DiCaprio eating raw bison liver for The Revenant or all of Jared Leto’s nonsense or Benedict Cumberbatch making himself ill from all the cigarettes he smoked for The Power of the Dog. I thought about Robert Pattinson’s joke that nobody goes method to play a nice person. I read through some lists of supposed method techniques and wondered why something as seemingly benign as maintaining a difficult accent in between takes became seen as both brave and unbearable. We’ve long since abandoned the true meaning of method acting, and we’re now mercifully at a stage where even the most wide-eyed critics retain a degree of cynicism towards this strain of tedious narcissism.

And yet it still works, or at least the foundations of this rhetoric are flexible enough to maintain their potency. It bolstered Daniel Day-Lewis’s career for decades, right up until his retirement following Phantom Thread. Still, colleagues talk of him with genuine passion. It was worth it for them, maybe because people actually like him. Sure, Time worked hard to sell him as such but there needed to be some level of truth to that for it to land (there’s a reason it’s never landed with Leto.) They’re selling the man as much as the actor, and defining the difference matters.

(Oscar number three. Image via YouTube.)

I think this Time profile strikes a solid balance between effusive praise of its subject and humanizing him so that he doesn’t seem entirely out of reach. It dives into his youth, growing up with a poet father and actor mother, and spending Summers in Ireland. He's open about the struggles he had as an adolescent after his dad died, and even talks about the now-legendary instance where he quit playing Hamlet on-stage because he apparently saw the ghost of his father (he describes it more as an abstract instance of confronting his own past, one he laughs about in hindsight given the weight of that moment in his life.) He also crucially avoids self-pity. When asked if his process makes him lonely, he answers in the affirmative but focuses more on the necessity of that for playing someone like Lincoln. It's refreshing, especially if you've read about plenty of far lesser actors putting themselves willingly through hell for a performance then moaning about it to the press (again, hello Jared Leto.)

Day-Lewis “retired” after his performance in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread, which, for my money, is one of his best. It was a strong note to end an incredible career, although nobody expected him to remain retired for long. And, true to our expectations, he is back at work with a film directed by one of his children. Good dad behaviour right there.

It seems doubtful that we’ll see another of his kind, in part because a lot of actors learned the wrong lessons from him. The industry still adores full-throated commitment to the craft, regardless of the results, but critics and audiences alike have grown impatient with this misguided version of the method. It won’t stop people from fighting for those Oscars (or winning them) but production standards have been forced to change in the wake of #MeToo and there’s far more scrutiny on the actors (who are usually cishet white men, it must be said) who demand that their colleagues adhere to their whims. How we define genius is something that desperately needs a paradigm shift, but in the case of Daniel Day-Lewis, at least that human element remained.

Thanks for reading. And thank you so much to everyone who has subscribed over the past few months. It’s been so humbling and encouraging to receive such support from readers like you who think my work is worth something. I hope you’ll stick around for future issues as we delve into everything and anything related to celebrity culture, gossip, and entertainment industry madness.

Great piece! Love him. Glad to not have that disappointed yet. The Boxer is my favorite probably bc it was my first DDL movie. The coiled, pained longing of Danny Boy Flynn towards Maggie? Whew. That did something to my 15 yo brain and high school boys were never good enough after that.