Issue 19: What Does it Mean to Be “Famesque” (Featuring Sienna Miller)

When you're famous but not a movie-star, and when everyone knows about your love life. Sienna Miller certainly understood that pain.

I’ve long had a soft spot for Sienna Miller. In the mid-2000s, when she was on the cover of every tabloid, I thought a lot about how weird her life must have been. While she was an actress, it was unavoidable that her status as a new A-Lister was built almost exclusively on the fact that she had a very public and oft-tempestuous relationship with the actor Jude Law, who she met while they made the terrible remake of Alfie. By 2009, the pair had split then rekindled their relationship. They'd become engaged but things had gotten messy when Law admitted to having an affair with his children's nanny (he even offered Miller a public apology for his cheating.) Miller had also had an affair with actor Balthazar Getty, the photos of which were a hot commodity among the press (he later went back to his wife.) No matter how much Miller worked on her craft and dedicated herself to acting, the papers spent precious column inches obsessing over her love life and her fashion. In fairness, it worked on my impressionable teen brain. Sienna Miller was the reason I had a boho skirt in the mid-2000s.

Nowadays, Miller is a solid B-List actress who sticks to her work and avoids the press whenever possible. She's more fully defined in 2024 as an actress than anything else. That certainly wasn't the case 15 years ago, when the Washington Post felt compelled to offer a brand-new definition for her kind of celebrity: the famesque person.

Washington Post. "Famesque: Amy Argetsinger on Celebrities Famous for Being Famous." August 10, 2009. Amy Argetsinger.

(Image credit: Maximilian Bühn via Wikimedia Commons.)

You know who Sienna Miller is, but you don’t know why you know her. That’s the basic thesis of this short but revealing piece that seeks to reclassify a 2000s version of a decades’ old concept. According to Amy Argetsinger, "There's absolutely no reason you should know who she is -- not even if you're a religious follower of the celebrity press that tracks her so closely." That seems unfairly dismissive to me. As Argetsinger notes, her career has frequently taken a backseat to her press notoriety but she seems ambivalent about how much of that was by Miller's own choice. She's "the most famous obscure art-house film star in history" according to Argetsinger, not a real star like Nicole Kidman.

Miller is the epitome of "famesque" because she is "a pioneer in a new kind of fame that is changing our celebrity culture, a fame that is increasingly disconnected from the star's success in the field for which he or she is ostensibly famous." Essentially, she has become a major part of the machine of celebrity but not through the work she's actually doing. Miller can be on the cover of every tabloid for months without releasing a movie and still bring in reader attention and fascination. She’s a cog in a shifting ecosystem that’s trying to keep up with the speedily changing times.

Concepts like the famesque and “famous for being famous” have existed for a long time, well before the age of social media, socialites, and soaps. In his book Dead Famous, historian Greg Jenner offered a study of celebrity dating back thousands of years, showing how fame and fandom is a crucial part of our sociological make-up. 18th-century preachers became nationwide celebrities through sermons. Gertrude Stein did ads for Ford. Lisztomania took over the continent. And throughout the centuries, there have been figures who have captured our imaginations even if we couldn't entirely explain why we knew them so well or how they became famous.

Consider the It Girl phenomenon, wherein young women of impeccable charm, beauty, and unknowability became icons almost by accident, from Evelyn Nesbit to Dianne Brill to Chloe Sevigny to Moo Deng (yes, she is listed on the It Girl Wikipedia page as an example so I am embracing it.) As I talked about in our issue dedicated to Sevigny and her It Girl legend, the title was typically bestowed upon women who were either part of nobility or a hot social scene that inspired a level of envy among the general public. In 2023, Matthew Schneier for The Cut, defined the New York "it girl" as being: "Famous for being out, famous for being young, famous for being fun, famous for being famous." It’s almost a perpetual motion machine, a self-feeding monster of exposure, content, and hype.

The general idea is that an It Girl or someone who is famous for being famous doesn’t have a “real job” or live off daddy’s money. Argetsinger's definition of "famesque" is of a similar vibe, but differs in that she generally applies it to those who did become established through what we deem traditional means of celebrity. Miller, for example, was working as an actress before she met Law and had done some modelling for the likes of Coca-Cola and the Pirelli Calendar. But the article is, rather bluntly, correct in noting that Miller's films were not what defined her in the public eye. "She's an actress, but odds are you've never seen a single one of her movies or TV shows." Maybe, by 2009, you'd seen Casanova with Heath Ledger or the delightful Stardust, but she wasn't a box office draw at a time when that was still a crucial part of an actor's career. Miller was famous because of Jude Law.

Argetsinger talks about the pre-2000s idea of "Famous for Being Famous" in terms of classic talk show and game show figures like Charles Nelson Reilly and Zsa Zsa Gabor. They could be relied on to tell good anecdotes on Johnny Carson's couch or give a quippy response in Match Game, but you wouldn't necessarily think of them as anything other than celebrities. Reilly was a beloved TV regular who worked with everyone, won Tonys and was an entertainment mainstay for over 50 years, but it could be argued that he was never a major figure in the business. As Argetsinger writes, "the FBBF always seemed to know how marginal they were -- that was their charm. And they never, ever made the cover of People." If we're to bring back the now-outdated notion of the A- to Z-List of Celebrity, the FBBF people would be C or D: name awareness, some fans, reliable presences on TV, and general eccentrics who are fun to hang out with. You wouldn’t imagine them being in the upper echelons of fame, at least not in terms of coverage or awareness.

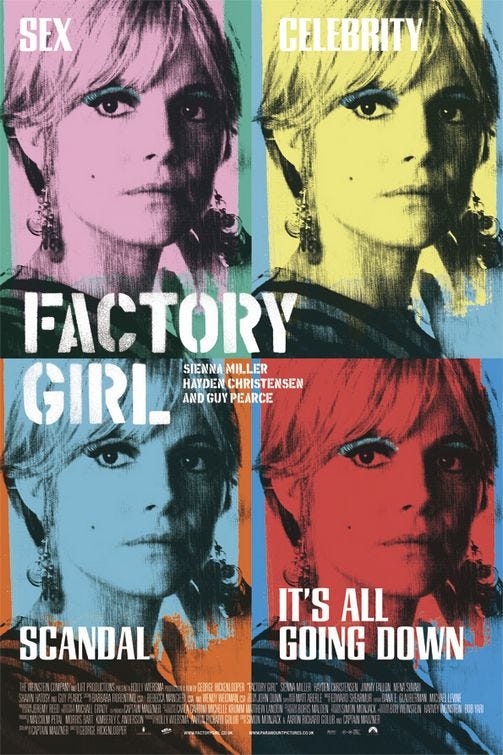

(Honestly, I could probably talk for hours about Factory Girl, the Sienna-related press surrounding it, and the Weinstein of it all.)

That seems to be the differentiating factor between FBBF and famesque: the latter can accrue all of the expected qualities of high-level fame, even if the reasons for doing so are ephemeral. Like I said, Miller was never off the front pages but it wasn’t for her work, and her presence in something like The Mysteries of Pittsburgh didn’t guarantee anyone would go to see it.

So, how does one get to this level of famesque? "The truly famesque possess the seeming gravitas that comes with a title and the suggestion of a job -- actor, singer, pro athlete. It's just that . . . you've never seen them act, or heard them sing, or watched them play. Instead: You read about them. A lot." This speaks to the changing market of celebrity tabloids and the media in this torrid decade. The magazines still ruled the roost but Twitter was now a thing, blogs like Perez Hilton were snarking up a storm (and getting a lot of attention for it), and reality TV was becoming evermore dominant. This is the time of The Hills, which made Speidi unavoidable, and Jersey Shore, which inspired genuine moral outrage. We had a new kind of celebrity with this brand of constructed reality television. These were people who were playing parts, twisting the truth, and offering a performance that was “real” despite being heavily teased out. They were primed to be famous and they wanted it. They didn’t run away from the paparazzi: they called them up and posed. This gave magazines and blogs alike enough content to keep them going for years to come.

But it’s still a different catch of fish from someone like Sienna Miller. Yes, she could give a fun candid interview and her personal life was capital-M Messy, but she wasn’t revelling in the attention. Actually, she was deeply repulsed by it. There was a kind of, for lack of a better term, respectability to her. Reality TV is “trash.” Actresses are “class.”

Still, as Us Weekly News Director Lara Cohen notes in the piece, she just had the stuff that people wanted. She was beautiful and a rising star in the UK who was London-based (helpful for photo agencies that are based there), stylish, and eventually one half of a power couple. Law was notoriously inescapable in 2004 and 2005, something that was even joked about at the Oscars (Sean Penn was weirdly pissed off about that, because he's a humourless thug.) He was getting tons of press as the hot new leading man on both sides of the pond and she was his co-star who made him look even better. It’s just good maths: "the power of celebrity dating, where "one plus one equals four"."

And hoo boy did this couple get into some drama. Law has famously never been able to keep it in his boxers, and Miller shagged a married man and got caught with him on a boat. During the early years of their relationship, the press also reported that Miller had cheated on Law with her Layer Cake co-star Daniel Craig. Nothing makes the tabloids happier than celebrity marital crises. It’s considered the right kind of high-low stakes drama that everyone can relate to and make moral judgments on. We’re still doing this, as evidenced by Ariana Grande and SpongeBob. So much of celebrity demands that we idolize some and demonize others. What better way to ensure that narrative than by plundering someone’s romantic life for content?

Crucially, for the piece, the primary defining quality of the famesque is simple: you need to be hot as hell. "The famesque are young, beautiful, and noticeably white -- a formula that seems to disproportionately draw the paparazzi and dominate the gossip magazines." Argetsinger offers a possibly exception to this rule with Kerry Washington, although we all know how that she was a few years away from being a household name thanks to Scandal. But there is something to this argument. We like looking at hot people, speculating about how they got and stay hot, and wondering how being hot impacts their lives. Plus, we're weirdly culturally taught to be mean to hot famous people and claim that they're either immune to our deserving of our cruelties because of it. Seriously, if I got £1 for every comment my work had received that amounted to some version of, "Who cares, they're hot", I'd be rich (and no, I’m not saying that pretty privilege doesn’t exist, it’s more that a lot of people think they can be as mean as they want if they view the other person as being too privileged to care.)

Alongside Miller, Argetsinger categorizes other members of the famesque division, including Jessica Simpson and Anna Kournikova. The latter, a tennis player who was fetishized heavily for her beauty, was often mocked for her on-court skills by the same people who leered at her like a piece of meat. Simpson had a solid pop career but Newlyweds and her post-divorce romances garnered more headlines (as did her weight, which we discussed in a previous issue.) Men can be famesque too. Ashton Kutcher is named as the main offender here, mostly because of his marriage to Demi Moore, although he certainly moved into another level via his investments, later marriage to Mila Kunis, and time on Two and a Half Men. Mostly, it does seem to be the denizen of beautiful white women, however, which is of no surprise to anyone. They’re easy to fetishise, to commodify, and to shame.

That’s also part of the Miller mystique at the time: because she was seen as being inexplicably famous, that it made it easier for people to dismiss her and treat her as somehow deserving of worldwide scolding. We hear variations of this a lot when it comes to this vein of celebrity: “Why are they famous? Why should I care? Can’t she just go away? She’s not talented.” And so on. It becomes a cycle: person becomes famous for their personal life, it overshadows their career, people get sick of them and assume they have no real career, and they keep getting headlines once the “backlash” hits. The system exists with or without your active participation. Miller clearly didn’t want to be a part of it in the mid-to-late 2000s.

To talk about Sienna Miller now is also to talk about how that barrage of press intrusion impacted her life. She was a key witness during the Leveson Inquiry, regarding the UK media’s oft-cruel and needless invasion of others’ privacy. Following a High Court hearing in May 2011, Miller was awarded £100,000 in damages from News of the World after the newspaper admitted hacking into her phone. As she told the Inquiry: "I would often find myself almost daily, I was 21, at midnight running down a dark street on my own with 10 big men chasing me. The fact that they had cameras in their hands meant that was legal. But if you take away the cameras, what have you got? You've got a pack of men chasing a woman, and obviously that's a very intimidating situation to be in."

In 2021, she took the Murdoch-owned News Group Newspapers to court. While she accepted a financial settlement from them, she admitted that she had wanted to go all the way to trial but that such things were unavailable to anyone who couldn't outspend a major conglomerate in lawyer's fees. "They very nearly ruined my life," she said of The Sun, the newspaper she alleged hacked her phone. She even revealed that the endless intrusions included a newspaper getting hold of her medical records, which proved at the time that she was pregnant. She later chose to have an abortion. Her choice not to continue with the pregnancy was, she told British Vogue, “in many ways impacted by that behaviour”. In the aftermath, “People on the street would shout ‘baby killer’ at me.”

In the ecosystem of the so-called famesque, where is the line in the sand? If it is widely agreed upon, by the press and public alike, that such figures are fair game, does gross and illegal invasion of medical privacy become just another news day? This wasn’t and isn’t exclusive to the kind of celebrity that Sienna Miller was, but there is a grain of truth to this notion that “certain celebs” are told to expect everything with a rictus grin and implicit nod of approval. To devalue someone’s personhood and their work is to make it societally acceptable to turn their agony into spectacle. Then again, isn’t this just fame in a nutshell?

(Sienna Miller giving her testimony at the Leveson Inquiry. Image via YouTube.)

How do we define famesque now? Are we beyond such things? I go back and forth. Fame means something quite different in 2024, when the internet and various forms of new media have led to a twisted kind of democratization of celebrity. There are hundreds of TV channels and streaming services. TikTok and Instagram are on everyone’s phones. A woman joking about spitting on a guy’s penis can become a millionaire. The 15 minutes of fame Andy Warhol promised us all is now a cottage industry you can milk into oblivion if you’re savvy enough. It’s fascinating to me but also f*cking exhausting. It’s my job to keep up with stuff like this and I physically can’t do it. Nobody can. Trying to keep up with all of celebrity now means knowing about Glen Powell and MrBeast, Charli XCX and Call Her Daddy, actors from The Office and cast members of Below Deck. The niches of fame are nicher than ever.

But I don’t think everyone else is expected to know it all. It is possible to stick to your little corner of celebrity and never have to worry about someone called the Rizzler (don’t ask.) Sometimes, you’ll read an explainer on the trend of the moment but there are far less figures who are deemed essential by the culture. Hollywood in particular is lamenting the lack of a new generation of Grade-A movie-stars to replace the likes of Tom Cruise and Will Smith. Maybe you’ll feel like Glen Powell is being shoved in your face against your will, but let’s be honest, that happens way less nowadays than it did when Sienna Miller was front page news.

We’ll always have a hierarchy of fame, but the barriers are evermore liminal. It’s possible to be an indie star with name recognition as well as a huge star with no box office guarantees. Bravo reality shows can be reported on by The New York Times. It’s the influencer era combined with poptimism. I’m not sure that meets the definitions of famesque, though. The idea of being famous for some amorphous reason that isn’t instantly known is just the norm for a hell of a lot of celebrities now. If someone like Sienna Miller – a pretty working actress with a more famous boyfriend – were to emerge in 2024, they would certainly be consumed and presented in a different manner. That’s not to say it’d be a kinder way. Misogyny in the tabloids has arguably gotten sneakier, more covert in its cruelty but no less pointed.

Argetsinger wonders what would happen if Miller were to become a "real" movie-star. "Will we lose interest? Will she stop saying provocative things? Stop wearing crazy clothes? Stop dating messed-up dudes? (Cohen's not worried: "She has a really great publicist. One of the best in the business.")" Well, what happened is that she just got on with life. She's still on Vogue covers, she gets good reviews for her work, and she's still extremely stylish. She seems to have the career that she always wanted: good directors, good actors, jumping between TV, film, and the stage. She has two kids who stay out of the public eye. Her love life is not seen as a big enough deal to warrant endless reportage. Frankly, that’s boring to the press. Maybe that became boring to the press, or perhaps she just wasn’t the celebrity for the moment as the 2010s began and things shifted dramatically. There were always other young women to throw to the wolves. Same as it ever was.