Oscar Seasoning: Is There a Right Way to Want an Oscar (And a Brief History of Awards Campaigns)

You have to want to win an Oscar but not be desperate for it.

I don’t for a moment believe any person in the film industry who says they don’t care about awards. It’s a near-impossible topic to be ambivalent about. You can hate the process and the butt-kissing and the sheer pageantry of it all but still seek validation from your peers. It’s nice to win stuff, and it’s exciting to be celebrated for your work, regardless of what field you’re in. There is a reason you don’t see a ton of people in Hollywood sitting out the Oscar cycle when the vaguest possibility of a nomination comes their way. It’s hard to say no to it all, but it’s also tough to exclude yourself from a key part of your job, one where all eyes will be on you and expectations are high.

In a recent article by Michael Schulman of the New Yorker, Bradley Cooper’s recent awards thirst and the social media mockery of his ambition was dissected (I delved into the topic myself in a prior newsletter.) What Schulman so elegantly conveyed was how thin the tightrope is for those who show themselves eager to engage in the process of campaigning for an Oscar. You have to be grateful but not grovelling. You must be humble but not so much that you seem disinterested in the cycle. You must work for it but not show the flop-sweat from your labours. Be eager but not so much that you seem desperate. Poor BCoop is failing on the last part these days, so it seems. We’re never especially kind to people who want to be great.

This is the quandary of the awards campaign: how do you do it right? Is there even a way to do so without ending up as a power-hungry villain or object of pity? Let’s get into it! But first, some history.

(Me too, Bradley.)

The Oscars exist because, in the 1920s, a few Hollywood studio heads wanted a way to negotiate on labour issues that circumnavigated those pesky unions. The Academy was set up for this job, and an awards ceremony was seen as a nice way of legitimizing affairs. Plus the film industry was now an official artform and cultural phenomenon after a couple of decades of scepticism, so why not get into some self-congratulatory back-slapping? Who doesn’t like a trophy? The early winners were all but hand-picked by the studio heads, a nice way to promote their work and crown the stars of the moment. Luise Rainer, for example, won two Best Actress wins in a row for some ropey performances (one in yellow-face) largely because MGM’s Louis B. Mayer was trying to sell her as the new Greta Garbo. Rainer had no interest in being moulded in this manner, and basically left Hollywood shortly afterward. Over the next couple of decades, the Oscars gained more clout, being seen as the top award in the film world, and soon, people actively wanted to win one.

Once you introduce an award, it doesn’t take long for people to start the work of winning one, and we all know it’s never just about merit (frankly, most of the time, one wonders if merit is even considered by Oscar voters.) The first Oscar ad ever placed in the trades was for 1935's Ah, Wilderness, but it received zero nominations. In 1940, RKO let the biz know about Ginger Rogers by filling the trades with ads crammed with glowing reviews for her performance in Kitty Foyle, and she won Best Actress.

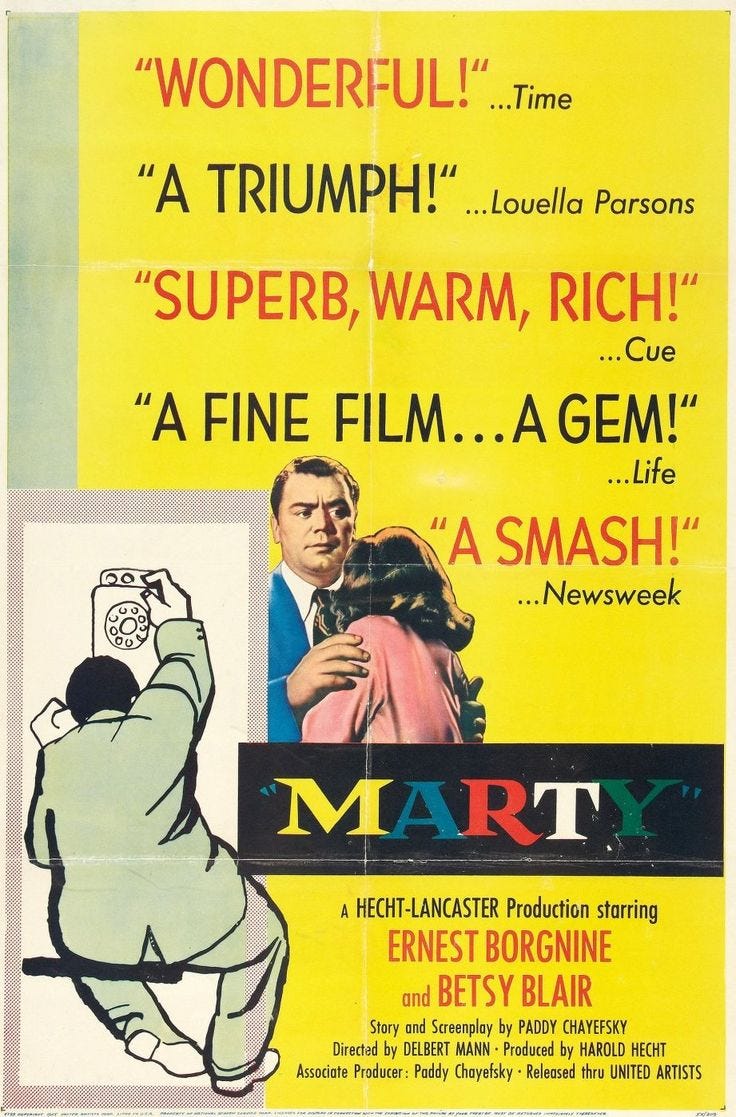

By the 1950s, stars began hiring publicists to help them grease the wheels and campaign to their colleagues for those precious votes. Humphrey Bogart, who had previously claimed he didn’t give a damn about the Oscars, hired a press agent when he was nominated for The African Queen (he won that award over the presumed victor, Marlon Brando.) In 1955, the movie Marty, a tiny-budgeted romantic drama based on a TV play, allegedly spent more money on its awards campaign than its entire production. Star Ernest Borgnine was seen at every party and became the face of the film, which paid off with wins for Best Actor and Picture. 1967's Doctor Dolittle, a notorious critical and commercial flop, got way too many nominations because Fox bought a ton of champagne dinners for voters.

The man who truly pioneered awards campaigning as a full-on business was, alas, Harvey Weinstein. Sadly, we can’t talk about this history without getting into the weeds of his tactics, as dirty as they often were. Miramax placed an intense amount of importance upon the Oscars as a way to draw more financial and industry-wide attention to his indie films of various kinds. He made it the norm to spend tens of millions of dollars on these campaigns, helping it evolve into a year-long business. His aggressiveness (in more ways than one) was implicitly condoned because it got results. Stunts like hosting member screenings in the Academy retirement home and ski resorts where all the celebs holidayed got the job done, as did outspending the competition on wall-to-wall ads and VHS screeners. What also worked were nasty and barely concealed smear tactics. This specific era is really in need of its own article, one that’ll probably be longer than my Master’s thesis. For now, just remember that Weinstein made it okay for awards season to be dirty and shameless.

After Weinstein’s decades of abuse and rape were fully exposed, Hollywood did get a little less vocally forceful with awards campaigns. It’s still a messy field with lots of mud-slinging, but you do get the sense that nobody wants to be seen crawling around in the dirt. That’s not to say that campaigning has lessened, nor have people stopped wanting to do everything in their power to win an Oscar. Again, winning stuff is cool and we all like it. Another thing I think has changed is the general public’s awareness of the process. The trades are read by everyone, and various aspects of the campaigning cycle are now codified to the point of parody (those roundtables, for example.) Visibility is key during this season and that means everyone outside of Hollywood can see it happening too.

What this also means is that we’re more hyper-aware of the emotional investment required to campaign. You do this because you, your team, and your studio want it. We joke about those actors who seem hungrier than their competition. I remember the Leo years. Bradley Cooper is the poor sap stuck with that role this season, but he’s never alone. Cooper’s problem (other than the fact that Maestro is Not Good) is that he’s wearing his heart on his sleeve and making all of the campaigning extremely public. That reads as desperate to many and that kind of earnestness is unforgivable. But he’s obviously doing other campaigning we don’t see, and therein is where the most votes are won. It's about going to all of the parties and film festivals, welcoming those voters into the fold, and presenting your case. You have to show you want it but not too much. It’s as much a performance as the one they’re nominated for. And almost everyone does it. Those who sit it out and hope to let the work speak for itself are drowned out by the politics.

There are, of course, other factors at play. Certain performance types do better than others (biopics, lots of method crap, a big transformation), and the Academy tends to steer clear of truly confrontational issues (which is why The Zone of Interest, which I believe to be the best of the 10 Picture candidates, will not win the top prize.) They love to see the labour of acting but not the work of campaigning. It’s no wonder so many people burn out from this process or start playing it dirty. It must be exhausting to go through months of this, only to fall at the last hurdle because your contemporaries thought you were too eager or not eager enough.

Personally, I have a soft spot for actors who just say out loud that they want to win. Frankly, I’d love it if Cooper just admitted he was eager to claim the top prize and the validation it came with. I’d find that far more honest and relatable than his current rigmarole of cringe. He will win an Oscar one day. That’s not in doubt. Eventually, he’ll get the Leo narrative of being long overdue and people will rally around him. He is but a cog in a broken machine with ever-moving goalposts (apologies for the mixed metaphor.) After Sunday, let’s hope all the nominees can just relax for a bit and not have to worry about upsetting some anonymous producer who clearly didn’t watch any of the movies. Imagine having to pander to the losers who couldn’t even bring themselves to finish watching a two-hour drama.

(Team Lily!)

The Oscars take place this coming Sunday night for Americans (it’ll be an early Monday morning trek for me – and I’m going to a concert on the same day, tiredness permitting!) I have one or two more Oscar Seasoning posts I want to get up before then, including my predictions so you can all judge me for how wrong I get it!

For those who may have missed it, I will also be reposting old pre-Substack issues of the Gossip Reading Club here as a perk for paid subscribers. The first reissue was free so you can check out my old post on the iconic Vanity Fair images of a pregnant Demi Moore and how they changed the business of the celebrity pregnancy.

If you’d like to support my work in another way, I have a Ko-Fi account.