Oscar Seasoning: My Favourite Films of 2024 (Expect Very Few Oscar Contenders)

A good year for film, a not-so-good one for, you know, the other stuff.

The end of the year is in sight. 2024 was, well, a whole thing, politically and philosophically. Personally, though, it was pretty good for me. I went to Madrid and Toronto. I had a lot of good times with family and friends. I saw some amazing concerts. I had some great professional moments, from appearing on BBC News and Radio 4 to making my debut on The AV Club. I’ve been in this business for 7 ½ years now, which feels like a lifetime for lowly freelancers like myself. Also, I saw a few films, so that means it’s Top Ten time. Yay.

Obviously, there were a ton of movies I just didn’t get to see, either because I missed them or they haven’t received a wide release in the UK (we don’t get stuff like Maria, Nosferatu, Nickel Boys, and The Brutalist until January.) Some titles I caught early at the Toronto International Film Festival. I’m sticking to US rules with my list, meaning only films that received American releases between 1st January and 31st December qualify. For those interested, my top three worst films of 2024 are Back to Black, Emilia Perez, and Vice is Broke (the last one hasn’t received a wide release yet, but still, f*ck that movie.)

My list is very me, it must be said, which means it’s largely indie and not especially Oscar-friendly. There are exceptions but as with many critics, there’s not a ton of overlap between my taste and that of the illustrious Academy. If only some of these works were Best Picture frontrunners. Still, I’m happy with my top ten. But it could all change on Christmas Day when the most anticipated artwork of our time premieres on UK TV: Wallace and Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl.

La Chimera

Bong Joon-ho once described the work of Italian director Alice Rohrwacher as "a mix of magic realism and neorealism, innocent characters butting up against corrupt behemoths." That’s a good way to describe La Chimera, a gentle but achingly moving romantic drama that captured my heart and held onto it tightly all year.

Josh O'Connor, who had one hell of a year between this and Challengers, played an Englishman in Italy with a near-mystical ability to locate hidden historical treasures in the Tuscan countryside. Fresh out of prison for tomb raiding, he reunites with his old gang of ragtag criminals to make a few quid by returning to their old ways. While he yearns for his lost love, he finds himself taken by Italia, an unpaid maid hiding her secrets from her employer and the world.

There’s a deceptive gentleness to La Chimera. It seems so languid and inviting, like a dream holiday, but slowly reveals a slyer and more satirical edge to its tale of treasures and worth. The group are thieves who see themselves as Robin Hood-esque but in a world where everything is for sale, is there really any nobility in their actions? The idea of even putting a price on something as treasured as one’s own history starts to feel sacrilegious. When the magical realism elements quietly enter the picture, it feels like an inevitability in this world, and I was enraptured by every second of it.

Every year or so, at least one film comes along where it immediately earns a spot in my 150+ long list of my favourite films ever made. La Chimera is definitely part of that illustrious class now. Sometimes, a film comes along and you just know it was made for you. What a treasure.

Evil Does Not Exist

Speaking of instant favourites, a couple of years ago, I went to see Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s anthology that was released in the UK in the aftermath of the surprise success of Drive My Car. I was the only person in that cinema, which worked out in my favour because I spent the final 30 minutes of it sobbing my heart out. The film just broke me open and felt finely engineered to get me, as the kids used to say, right in the feels. I liked Drive My Car, but after Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, I knew that Hamaguchi had me for life. So, of course his 2024 title made my list.

Evil Does Not Exist is a little more ephemeral than its predecessors, although it’s similarly as unhurried and focused on the seeming mundanities of life as that duo. A cast of largely non-professional actors populates this drama about a small village in the Japanese mountains trying to fend off a proposed glamping camp that none of them wants. Two representatives for the site developers are sent to alleviate their fears (largely by ignoring them) and soon find themselves shifting allegiances to the locals.

This is an eco-parable but it's also far more enigmatic than its initial set-up would suggest (with an ending that confounded many but left me breathless.) The seeming simplicity of the production, the dialogue, and the acting create a wholly human portrait of a community in the face of potential annihilation. Their concerns are ignored and dismissed with a “thank you for the feedback” line that nobody believes, and the confirmed dangers a totally unnecessary glamping site would bring to their way of life are seen as frivolous in the face of potential profits. Can’t imagine why that would resonate in 2024…

What bowls me over about Hamaguchi films is how recognisable they all are. That intimacy he creates is so painfully familiar that it often feels intrusive. Simple conversations offer tiny revelations, delivered as casually as a “hello, how are you?” But Evil Does Not Exist is also existentially kind of terrifying. It cannot answer the dark questions it poses and nor should it be their responsibility. The fault lies with the capitalistic forces trampling on the countless voices who reject their depressing norm. Terror happens because a lot of people are just doing their jobs.

The craft is impeccable too, with some of the most beautiful cinematography I saw all year, plus a score by Eiko Ishibashi that is as ambiguous and atmospheric as the visuals. Hamaguchi-san, you have my sword forever.

Love Lies Bleeding

(Image via A24.)

How was I ever going to say no to a lesbian bodybuilder noir? Rose Glass decided to fling everything at the wall and see what stuck with Love Lies Bleeding, a film for which the phrase “tone it down” does not exist. My colleague Jason described it as Mandy meets Bound. What more could you want?!

Kristen Stewart and Katy O’Brien f*ck the screen as the star-crossed lovers whose muscled passion is interrupted by steroids, murder, and corruption. This is Hot Mess cinema, all glaring neons, clogged toilets, and pulsing delts. It’s no surprise to me that the film ended up being a favourite of John Waters because this feels like the natural descendant of something like Female Trouble or Multiple Maniacs. Be gay, do crime? It’s a philosophy.

The film is both exceedingly horny and utterly hilarious, with Stewart giving one of her finest comedic performances as an over-it dyke who wants to get through life without having to pick brains off the carpet again. For every moment of shock and grotesquery, like Dave Franco losing his jaw, there’s one that is practically giddy about how far it can push the audience to embrace its inner freak. Comparisons to Cronenberg were made because of the steroid-induced transformation of O’Brien, which felt a tad lazy. But like Cronenberg, Glass is not-so-quietly enthralled by the changes. What if juicing up is a form of gender and physical euphoria? She-hulking out is good, actually. Certainly, it seems preferable to the repulsiveness of patriarchal rule.

Love Lies Bleeding doesn’t really build to a cohesive whole but the sum of its parts is too fascinating and addicting to dismiss. Amid the endless hand-wringing over eroticism in mainstream cinema and the “sex scenes in film aren’t necessary” scaremongering, Rose Glass put her stake in the sand in favour of sex, drugs, and pull-ups.

Babygirl

(Image via A24.)

Speaking of sex scenes in films, Nicole Kidman also let the world know that she’s Team Freak. Then again, she’s been waving that flag for 30 years now and shows no signs of slowing down. One of the nerviest megastars in Hollywood delved into the world of BDSM with an erotic drama that both mocked the conventions of the genre while placing them thoroughly in a 2020s, post-#MeToo context.

Romy has everything the modern woman could ask for except for one thing: her hot, loving, and considerate husband can't make her come. Desperate to retain control over her life, she finds herself struggling to be the boss when Samuel, an intern at her company, begins to worm his way into her psyche (and pants.)

Babygirl, written and directed by Halina Reijn, has no easy answers to the questions of power and pleasure. Romy is clearly in the wrong for engaging in an affair with an employee and yet he has an undeniable power over her. Is it a reinforcement of the gender binary? A fantasy gone wrong? Or just the prioritising of pleasure above all else? It hardly matters in action, especially as the two subjects seldom seem in control of their actions. How do you engage in a dominant-submissive relationship when neither of you know the rules? It’s as though the audience is learning along with the test subjects.

And the sex is great. It’s funny, all-consuming, invigorating, kind of weird, and surprising. There’s liberation in being on your knees. Kidman is excellent, a woman who wants to find the balance between giving up control and retaining it. She lives life with an icy but somewhat approachable demeanour, the platonic ideal of the girlboss, and her life is glossy like a magazine. As the sheen wears away, her self-discovery takes her down some dark paths. But this is no erotic thriller from the ‘80s. Every moment you think is going to swerve into such tropey territory takes a sharp turn away from it. That might prove unsatisfying for some but that was the point for me. If life is a series of cockblocks, it makes the final orgasm that much more thrilling.

Bird

(Image via Mubi.)

Andrea Arnold is known and beloved for her gritty tales of working-class British realism and life on society’s margins. Bird is no different. It takes place on a council estate where the 12-year-old Bailey lives in a squat with her very young and not particularly responsible father Bug (Barry Keoghan.) Her mother lives elsewhere with her young siblings and abusive boyfriend. She doesn't seem to go to school. Bug is getting married, much to Bailey’s chagrin, and his big money-making plan involves a toad he has to sing Coldplay songs to. Left with little to amuse herself or find her sense of being in this messy life, she finds herself acting as a guide to Bird (Franz Rogowski), a mysterious traveller looking for his family.

A lot of Bird is typical Arnold: the spontaneous sense of place and dialogue, the empathetic gaze towards lives of poverty and strife, the humour amid the peril, and the cinematography that finds beauty in the strangest places. Unlike, say, American Honey or Red Road, Bird has a fascinating sentimental streak. It’s not soppy or romanticizing of its setting; it’s more an unexpected dash of the fairy-tale to proceedings that feels new to Arnold’s worlds. A lot of Bird feels more like an Alice Rohrwacher film, which obviously meant I was a big fan. It’s her most open-hearted work, and a reminder that Arnold is one of the best filmmakers in the business.

A Different Man

(Image via A24.)

In her wonderful book Doppelganger, Naomi Klein talks about the perils of the mirror world, where everything seems to be ostensibly like that of our reality but twisted in a way that leaves us all adrift. A Different Man imagines the double conundrum through the eyes of a man who got everything he wanted and has nothing to show for it but self-loathing and bafflement.

Sebastian Stan does career-best work as Edward, a depressed introvert with neurofibromatosis who feels the life has played a cruel joke on him. His new neighbour is clearly put off by him but also fascinated enough to plunder his life for inspiration for her terrible plays. After a near-mystical experimental treatment cures him and leaves him with the face of noted hunk Sebastian Stan, Edward reinvents himself as Guy and auditions to play himself in Ingrid's schlocky piece. But then in walks Oswald, another actor with neurofibromatosis who is funny, charismatic, and dreamy.

A Different Man is caustic, weird, and bleakly funny. Edward becomes haunted to the point of madness by the mere idea of Oswald, a man who he feels should be crushed by his condition but instead gets on with life and is loved for it. Is self-confidence all that he needed to have a good time? Was it really so easy? Oswald certainly makes it seem so, as played by the light-on-his-feet and charming Adam Pearson, who is appealing but also just smarmy enough to make you think that Edward’s paranoia isn’t entirely without merit.

Director Adam Schimberg also has a lot of fascinating ideas regarding both creativity and how ableism impacts it. “Disability narratives” are often written by able-bodied people who prefer inspiration porn over anything with nuance. Ingrid’s play starts out as such and evolves because, shock horror, having a guy who knows what he’s talking about involved in it makes an impact. Who gets to tell whose story? And why? It’s not that surprising to me that the mainstream awards bodies have largely blanked A Different Man since it’s essentially a giant F You to their status quo. Something this unsentimental and occasionally mean is probably too good for them.

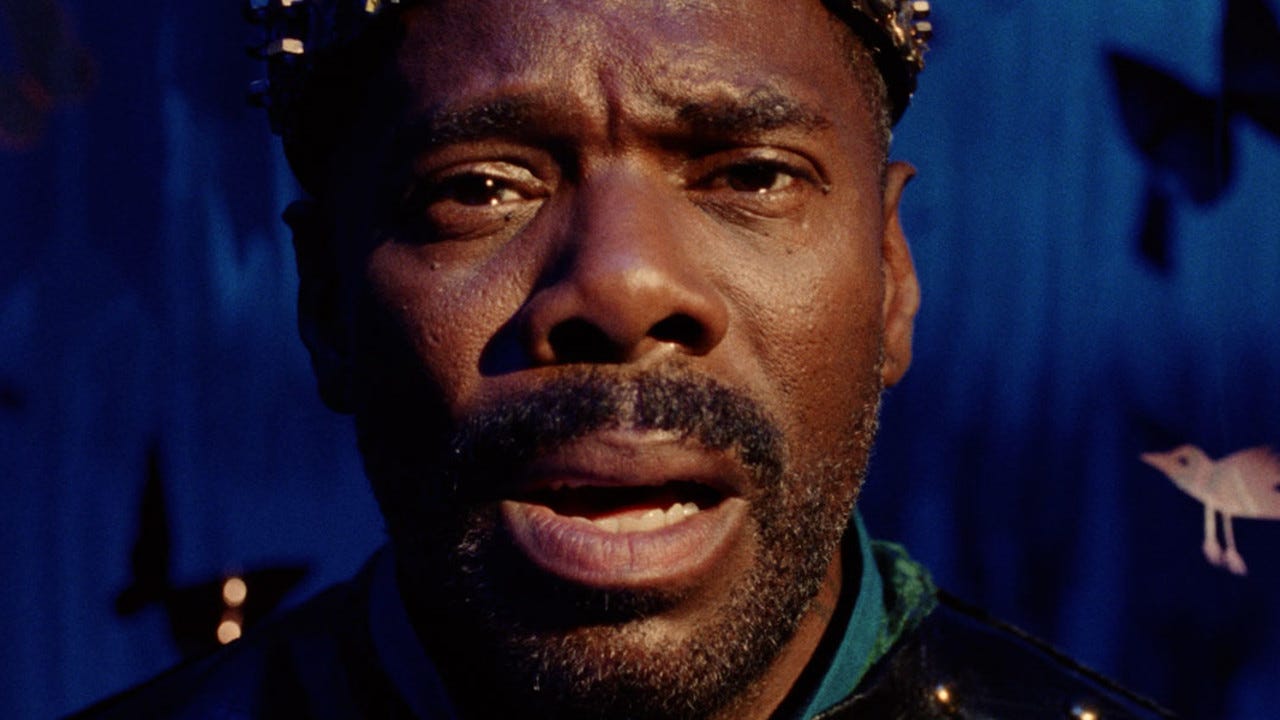

Sing Sing

(Image via A24.)

With the Rehabilitation Through the Arts program (RTA), thousands of inmates at America's most intense maximum security prisons have put on plays behind bars. Greg Kwedar's drama uses this real group and many of the men who performed with it to show the revitalizing power of art for those who need it the most.

The ever-magnetic Colman Domingo headlines Sing Sing in one of his best performances but the lion’s share of the cast are non-professionals who cut their teeth with the RTA. It would have been very easy to turn this film into a saccharine “inspirational” drama designed to make audiences feel smug and superior. It’s to Kwedan and his cast’s credit that Sing Sing feels so lived-in and authentic. Life is hard in prison and the glimmers of hope and satisfaction these men can find amid a broken system are to be treasured. Their plays are scrappy but earnest, a chance for these men to be something they’d otherwise never have.

Sing Sing is actually a very traditional crowdpleaser but the best possible version of one. It’s easy to watch it and imagine the “Hollywood” version we could have gotten had the stars not aligned properly. Mercifully, we got the one where the men who actually went through this get to tell their own story and do so without saccharine side-steps or audience hand-holding. In a just world, Domingo wins Best Actor and this ensemble become regular features on screens big and small.

The Room Next Door

(Image via Sony Pictures Classic.)

If I were to pick one filmmaker as my all-time favourite, it would probably be Pedro Almodovar. I own every movie he’s ever made and they have their own special shelf in my living room. Still, I was apprehensive about his English language feature debut, The Room Next Door, having found his shorts left me wanting. While this film is still not top-tier Almodovar, mid-level Pedro is better than 80% of directors working today.

Tilda Swinton and Julianne Moore are the actress dream team as a pair of friends who reunite later in life when one of them is diagnosed with cancer. As her condition becomes terminal, she decides that she wants to end her life on her own terms but doesn’t want to do so alone. This is a love story between two friends whose mutual need for one another reveals the true strength of the bounds between women. Sometimes, the great romance in your life is that of platonic friendship.

Almodovar’s mannered dialogue can feel stilted to some but in this vaguely unreal world where everyone speaks like a New Yorker essayist and has a beautifully decorated home, it makes sense. This is soap opera, as Pedro loves, but far more melancholy than, say, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. I think of The Room Next Door as being his Old Man movie, the kind of film that could only have been made by an elder statesman of the artform who is growing increasingly aware of the impending arrival of death. It feels like the feminine version of Pain and Glory, his semi-autobiographical drama about an artist fighting between creativity and sickness. We all hope to meet death as a friend after a long and full life, and The Room Next Door shows that the way we leave this planet matters as much as how we lived on it.

The Substance

(Image via Neon.)

I’m not sure I had a more raucous cinematic experience in 2024 than I did watching The Substance at TIFF. I’ve written about it before so I won’t bore you with it here, but seriously: the sheer riot of that screening will stick with me forever. The Substance is essentially a 21st-century hagsploitation flick, the 2020s version of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane but with more viscera. It’s repulsive, camp, as deep as a puddle, unbearably tragic, and hilarious. That it’s not an Oscar contender is proof that good things can still happen in our modern hellscape.

The Substance is relentless in its body horror but also its scathing disdain for our culture-wide sickness that treats mutilation and exploitation as far more preferable to ageing. The heightened Hollywood created by writer-director Coralie Fargeat is not that different from the one that exists. It’s a world where subtext is for cowards because humans are seldom so subtle in practice. Demi Moore gives a career-best performance in a meta exploration of her own life and body, partnered up with her young hot adversary Margaret Qualley, who continues her own gung-ho reign as a nervy actress who’s up for everything.

So, you know that one weird tech bro who’s spending millions of dollars to reverse the ageing process so he can live forever? You know, the guy with the odd puffy face who was taking a ton of his son’s blood? Whenever I thought about The Substance, that dude would pop up too. In the film, it’s ambiguous as to whether or not Elisabeth Sparkle and Sue actually share a consciousness. You could read their war with one another as a symbol of their mutual resentment for how older women are seen as disposable and how the inevitability of aging leaves us all trapped in the system of our own making. For me, I read it as being similar to the blood guy. He doesn’t go out, he has no love life, no hobbies. He doesn’t treat himself to a fancy meal or glass of bubbly. He’s spending so much time and effort on staving off aging that he’s now living like an infirm person. Elisabeth doesn’t find freedom with her new counterpart or a chance to let loose without the world’s expectations on her shoulders. There is no joy or satisfaction to be found in giving up on yourself for fear of being “old.”

That’s partly why The Substance lingers for me. Yes, the blood and prosthetics are amazing, and the balls-to-the-wall madness of the final act is one for the ages. But at its heart, it’s a story about how patriarchal rule is a waste of f*cking time. The best thing we can do is spit in its face (or throw body parts.)

Queer

(Image via A24.)

Daniel Craig’s post-Bond freak era is one of my favourite actorly developments of the 2020s. It became clear to everyone that Craig’s time as 007 wasn’t as creatively nourishing for him as he desired. Certainly, before he donned the tux, he was largely known for character-driven work and the occasional hot dude platform (remember when he was in the first Tomb Raider movie?) One can hardly blame Craig for wanting to strip himself of the Bond image as thoroughly as possible, and he’s done that by playing roles that are, to put it bluntly, very queer. He’s eschewing all signs of the toxic masculinity that defined Bond in favour of men who either reject that convention or subvert it in fascinating ways. Enter Queer, Luca Guadagnino’s messy but fascinating adaptation of the vaguely autobiographical William Burroughs novel.

William “Bill” Lee is a man of another time. A handsome but ageing American writer wasting away in Mexico City of the '50s, he spends his days drinking, gossiping, and trying to pick up younger men. He quickly becomes infatuated with Eugene Allerton (Drew Starkey), an all-American boy with zero body fat and adorable round glasses who is ostensibly straight but not uninterested in the older man. To say a romance follows wouldn’t be accurate. Nor is there much of a plot to speak of. Bill wants: he wants Eugene, he wants heroin, and he wants to uncover the mysteries of the universe via the ingestion of ayahuasca. His is a life of languid self-destruction.

There’s a lot about Queer that is messy, sometimes deliberately so but not always. The intrusion of modern music from the likes of Nirvana didn’t work for me, especially since the score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross was strong enough without them. Guadagnino is not above a trick or two, and it largely works when it comes to the increasingly unhinged and emotionally desperate tone of Queer. Wasting away in paradise has its downsides.

It almost goes without saying that Craig is excellent here. He’s so good at conveying Bill’s strain of charm that was once irresistibly potent but is now losing its power. It’s the flipside to the icy cool force of Bond, the seducer who doesn’t always get what he wants because he lives in the real world. He makes for an able anchor as the film descends into proud absurdism in its third act, when Bill ventures into South America to locate the drug he thinks will answer all his problems (shout out to a scene-stealing Lesley Manville as the greasy scientist with an adoring younger lover whose expertise Bill seeks.)

Queer is not the best Burroughs adaptation (that honour still falls to Cronenberg’s take on Naked Lunch) but it still feels like a minor miracle for all its faults. A lot of films on my list this year were Too Much in the best way possible, and this was no exception.

Honourable mention: Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Human

Vampires are back, baby! As a die-hard lover of all things bloodsucking, 2024 has been a great year for me. We got movies like Renfield and The Last Voyage of the Demeter. Romantasy got it on some classic vampire romance action. The second season of Interview with the Vampire became my entire personality. Last year at TIFF, I saw this delightful Quebecois dark comedy that received a limited release this Summer, and it was even better the second time around.

Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person is about… well, it does what it says on the tin. Sasha (Sara Montpetit) finds that she cannot kill people for food. Her fangs won't emerge at the prospect of a terrified human. After her mother decides to cut off her blood supply in the hopes she'll finally get over her inconvenient empathy, she meets Paul, a depressed teenager who seems curiously willing to befriend her.

The feature debut of Ariane Louis-Seize reminded me a lot of another of my favourite vampire films with a long title, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night. Both have a melancholy quality that taps into the inherent isolation of the vampire, particularly for "young" women. Humanist Vampire is a little more hopeful than its Iranian skateboarding Western counterpart, however. Sasha isn’t miserable about being a vampire or bereft of familial support. She’s just troubled by the thought of her food suffering for her benefit. There’s a lot of humour mined from her fears, contrasted by her family’s serial killer casualness in mass murder (shout out to her fabulously murderous cousin and her unexpected dirtbag fledgling.)

One of the reasons I so love vampire stories is because of how that central metaphor can represent pretty much any idea or contemporary concern you have. Honestly, I’m surprised we haven’t gotten more vampirey stuff in the millennial/Gen-Z era of online isolation, late-stage capitalistic nihilism, and political disaster. Humanist Vampire is at its core a simple story of finding your person and feeling less like a freak for it, but that idea endures for a reason and feels more pressing than ever to the likes of me. I hope this one finds its audience outside of cult movie circles, if only for the amazing soundtrack and hilarious opening scene.

What were your favourite films of 2024? Let me know in the comments.