Oscar Seasoning: The Zone of Interest Will Haunt You

Jonathan Glazer's drama about living a picturesque life next door to a genocide might hit too close to home for some.

WARNING: This post contains spoilers for The Zone of Interest.

I would love to know what the experience of watching The Zone of Interest was like for people who had no idea of the film's plot. I imagine it must have happened to at least some people. Details of Jonathan Glazer's latest drama (only his fourth feature film in 25 years) were scant for a long time. Even the reveal that it was adapted from a book by Martin Amis didn't provide much guidance because Glazer's last adaptation, Under the Skin, was only loosely based on its source material. Perhaps someone sat down in the theatre at the Cannes Film Festival, where the film had its world premiere, with no idea what to expect.

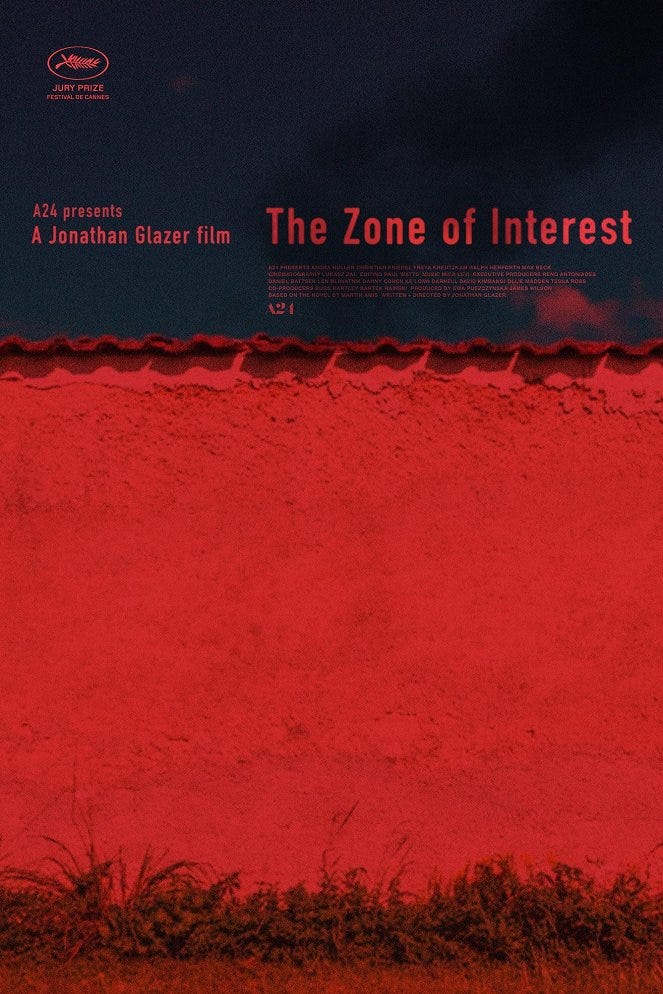

(Source)

The Zone of Interest opens on noise. The eardrum-scraping sound design, accompanied by Mica Levi's score, is designed to induce pure unease. It's mechanical, repetitive, like metal on stone at times, and punctuated by bursts of something that can only be described as pain. Then it gives way to birdsong and we see a happy family relaxing by a beautiful riverside. They enjoy themselves then go back home to their impeccably constructed house. The mother tends to the garden. The kids play alongside her. The servants prepare dinner. It's practically provincial, except for the chimneys in the background. And the billowing black clouds. And the screams.

This is the home of Rudolf Höss (played by Christian Friedel), the Nazi officer and longest-serving concentration camp commander at Auschwitz. He, his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), and their five children have made their home right next to the camp. They don't seem to notice the gunshots and graves behind the wall that borders their slice of paradise. Hedwig shows off her new garden to her mother and proudly notes how she has been nicknamed the "queen of Auschwitz." One of the kids plays with a collection of gold teeth. The servants get to pick one item of clothing that has arrived from the camp to take home. And throughout it all, not pausing for a moment, is the noise. They fall asleep to the screams, to the searing red light of the furnaces that never stop burning.

It's hard to write about this film without referencing the banality of evil, the concept forwarded by philosopher Hannah Arendt while she reported on the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Her thesis was that Eichmann, one of the main architects of the Holocaust, was not driven by sociopathy or ardent anti-Semitism but the mundane self-interests and pack mentality of most humans. It was not simply that he was "only obeying orders": he was also obeying the law, doing what his job and his country asked of him. This idea is, understandably, pretty controversial and many experts have pushed back against Arendt's summary of Eichmann (he was most certainly as anti-Semitic as they came, for instance), but the basic idea of evil as something so painfully normal stuck around for a reason. It's not that evil like this is banal itself but that our motivations for engaging in and exacerbating such cruelty are seldom as fervent as imagined.

(Image via A24)

You can imagine how Arendt would feel watching The Zone of Interest. Here is a film where the most horrendous acts in human history have become white noise to those benefitting from genocide. Hedwig at one point brags about finding one Jew’s diamond ring hidden in their toothpaste tin and how it’s encouraged her to ask her husband to bring back more toothpaste to their home in case they find another goldmine. She encourages her visiting friends to laugh at one of her pals choosing a dress from “some little Jewess” that was too small for her. None of them ever comment on the noise or smell. Hedwig’s mother is an exception, but even her own growing unease with her daughter’s flashy new home doesn’t climax in a confrontation. She simply leaves in the middle of the night without telling anyone.

Is this banality? In a sense. I think a lot of people have twisted Arendt’s ideas to mean that banality is interchangeable with ignorance. Glazer makes it clear that Hedwig is culpable in this genocide, particularly when she lambasts one of her Polish servants by letting her know she could have her husband scatter her ashes in the river. Höss is confronted by the ramifications of his eager professionalism but any reaction is purely self-driven. He takes his kids swimming in the nearby river but pulls them out when he discovers ash and human remains within the waters. His concern is for the kids, not the corpses. He is portrayed as a man who loves his job, who wants to keep doing it and be as efficient as possible, even when it clashes with his desire to be a family man. There is a banality to this idea, something that feels weirdly common, but not in its execution.

I’ve seen some critics condemn the film for not showing more of Höss’s anti-Semitism but I don’t think a ton of slurs would be necessary to do what the film already conveys so well. Sure, he’s just obeying orders, but he also clearly likes the results. He has a front row view to them from his bedroom window. Jewish prisoners are sent to his office for him to rape. The total detachment from humanity is a crucial quality of Arendt's thesis. You become better at being evil when you view it in such simple terms. We don't go into the camp but we see Höss take meetings with architects and fellow officers to discuss camp expansions and the Final Solution.

The entire thing is shot so straightforward, with no aesthetic add-ons or cinematographic flair. Shots are mostly stationary, with cinematographer Łukasz Żal keeping the camera running Big Brother-style, like a voyeur into this bad dream of a family home. There have long been arguments about whether or not it's possible to make a truly anti-war or anti-Holocaust film. How do you dramatize the unthinkable without making it glossy and dramatic in the ways that cinema demands? Glazer's solution is to commit to that intense formalism. It’s all natural light and colours. Discipline, through and through.

In the final scene, Höss attends a party (complete with swastika ice sculpture, of course) but finds himself disconnected from the fun. He calls his wife to let her know that he’s coming home because his work will allow what was nicknamed Operation Höss to go ahead. Hedwig is pleased but confused as to why he woke her with such news. He admits that he couldn’t focus on the fun because he kept thinking about the quickest way to gas all of the attendants. As he leaves his office, he stops to vomit but nothing comes up. He retches, unable to get whatever is stuck inside of him out. He peers into a dark corridor and suddenly, a door opens to reveal a group of cleaners and janitors in the present, working at what is now the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. They hoover the floors by displays full of shoes. One woman cleans the glass that separates future visitors from a platform full of old crutches. Another gives a quick wipe to the furnaces. Then we're back in Berlin and Höss walks away.

Did he glimpse into the future to see what his professional masterplan led to? Was he impacted by it? Glazer suggests not. That would be way too easy a way out for this guy, who doesn't even deserve the physical catharsis of vomit. His dream job is now the workplace for others, but their mundane focus on their work is not out of callousness or hatred but a stridently professional desire to preserve that which must be remembered. It’s a sign of respect, something Glazer clearly has for this story and what happened behind the walls of the Höss home.

It feels weird to see a film like this then go, “so, what about its Oscar chances?” One of my least favourite things about awards season is how it reduces complex storytelling and ambitious intentions down to tropes about winning little statues, as though that’s all film is good for. Certainly, I think The Zone of Interest is an excellent work deserving of acclaim. The sound design alone should win all the awards (all credit to Johnnie Burn, who also did the evocative and unsettling sound work on Jordan Peele’s Nope.) The Academy, of course, isn’t one for truly provocative or bold films. Plus, I’m not sure how many people could put their vote behind this while ignoring its forever-relevant messages about complacency and near-trite support for murderous atrocities. I get the sense a lot of people will watch this and think it has nothing to do with the current day in Gaza. When I saw Hedwig trying on her new battered fur coat (in need of a wash and some basic stitch mending, she tells her servant), I couldn’t stop thinking about this video of an IDF soldier using a still-saw to break into a Palestinian’s safe. Was Hamas in there, pal?

The industry loves to herald war films during awards season. Check out the success of All Quiet on the Western Front last year. But they prefer historical dramas where the “it’s all so relevant to today” line is a little more vague than what The Zone of Interest is presenting. A film about the damning culpability of those who would later claim they were following orders or just didn’t know what was happening in their own backyard? That might be a touch too pointed. We’ll wait and see tomorrow when the nominations are announced.

The Zone of Interest is playing in limited theatres across America. It opens in the UK on February 2nd.