Reading Hollywood: The Killing of the Unicorn (Dorothy Stratten, Peter Bogdanovich, and an Infamous True Crime Case)

An out-of-print memoir on one of Hollywood’s most infamous crimes is a messy, self-serving, and deeply tragic read.

(Content warning: This issue contains descriptions and discussions of sexual assault, murder, and violence against women.)

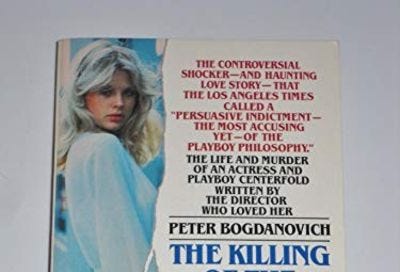

There are a few pieces of pop culture that have been my white whale over the years, those rare-to-find titles that remain shockingly inaccessible even in the digital age (physical media matters, kids.) One of these is The Killing of the Unicorn, the non-fiction memoir of sorts by director Peter Bogdanovich about his late girlfriend, the actress and Playboy model Dorothy Stratten, who was violently murdered by her estranged husband. Call me grotesque but as a celebrity gossip expert, a film critic, and someone who has consumed way too much true crime, I’ve always been fascinated by this horrific case. Even by the standards of Hollywood tragedies, it was bleak, and it cast a large shadow over the entertainment world. A report on the murder won the Pulitzer Prize (I talked about it here.) Bob Fosse made a movie out of that which tanked his film career. There are podcasts, TV specials, armchair detective forum threads, and the now-expected cycle of the true crime content complex at play. So, it was intriguing to me that the book written by her partner, an Oscar-nominated director who became an indelible part of her story, was so tough to read. Was there a reason it was out of print? I found a copy online (and paid a bit too much for it, it must be said) to finally find out for myself.

Have you ever read a book and truly wish it had never been published? This was… well, it was something else.

But first, some background.

Dorothy Hoogstraten was a young Canadian woman working at a Dairy Queen when a small-time pimp named Paul Snider discovered her and immediately decided to make her his latest meal ticket. He badgered her into posing nude and sent her images to Playboy, where Hugh Hefner took a fancy and invited her to Los Angeles to work. Changing her name to Stratten, she became Playmate of the Month and later of the year for 1980. She started work in films and was cast in They All Laughed, a comedy written and directed by Peter Bogdanovich, best known for The Last Picture Show and Paper Moon. Unhappily married to Snider, who tried to model himself as her manager, Dorothy fell for Peter and they began an affair during production. After Snider sent private detectives to dig up dirt on the pair, she decided to leave him. When she returned to Los Angeles, she went to meet with Snider to discuss divvying up their (read: her) finances. He murdered her with a shotgun, then killed himself. The crime scene showed evidence that Snider had sexually assaulted Stratten both before and after her death. She was 20 years old.

By the time Bogdanovich released The Killing of the Unicorn in 1984, Stratten’s death had all but become Hollywood myth. There had been two movies made out of the story: A TV movie starring Jamie Lee Curtis, and Star 80, Fosse’s devastatingly bleak study of toxic masculinity that is simultaneously brilliant and kind of evil. Bogdanovich had gone bankrupt trying to release They All Laughed on his own after its studio abandoned it, fearing that audiences wouldn't want to see a light-hearted comedy starring someone who was violently murdered. Bogdanovich wanted to set the record straight, to let people know that Dorothy was more than just an object of lust and tabloid speculation. He wanted the world to know of their love and her talent, but also her seething hatred for the institution that made her famous. The Killing of the Unicorn is, perhaps more than a memoir, an anti-pornography manifesto. Snider was a murderous monster, but Bogdanovich spares his most vicious ire for Hugh Hefner.

After the fall of the studio system, Hollywood blossomed with the promise that anyone could become a star now that the shackles of the old ways were broken. It seemed as though anyone could create the next model of entertainment. For Hugh Hefner, he decided that Playboy could be that model. Playboy was founded in 1953 and its first centrefold was, famously Marilyn Monroe. She didn't pose for the magazine. She had posed nude for a calendar before she became famous, and Hefner sold his new venture based on the promise that you too could see unedited pictures of a megastar in the raw. The Hays Code combined with the stranglehold of the studio system meant that seeing someone like Monroe naked was a fantasy. Now, it was reality, and Playboy's first issue sold out in weeks.

Playboy was sold as a classy magazine, for the gentleman about town who wanted to read John Cheever's short stories alongside witty political commentary and, yes, tits. Some of the most beloved writers in 20th-century fiction published shorts with Playboy. They pushed for First Amendment rights as well as support for the legalization of pot and gay liberation. By the late '70s, circulation was declining thanks to far dirtier competition from the likes of Penthouse and the rise of the mainstream adult movie. Remember, Deep Throat was one of the highest-grossing films of 1972 (a film that has since been revealed to be an act of rape against its unwilling star, Linda Lovelace.) “Porno chic” was in, and Playboy seemed a bit too stuffy for the liberated ‘70s, so it seemed.

But Playboy was still a big brand, bunny ears and all, and Hefner wanted to leverage that into Hollywood clout. It didn't seem entirely impossible. Playboy had made stuff for TV, and they had decent success there. They started funding movies, including the Monty Python film And Now for Something Completely Different and the Roman Polanski adaptation of Macbeth. What Hefner wanted most, however, was a home-grown talent he could act as a Svengali for, a real star who would represent Playboy to Hollywood through mainstream projects. Dorthy Stratten was that woman.

This is a lot of set-up for The Killing of the Unicorn, I admit, but it’s necessary to understand why Bogdanovich positions Hefner and Playboy as being so complicit in Stratten’s murder. Hefner was not only part of the systematic dehumanizing of Stratten but the poisoning of the grand promise of the sexual revolution. He briefly details Hefner’s upbringing and establishment of the magazine, leading into his remoulding of himself as the ultimate orgiastic gentleman who was both well read and ceaselessly horny. Bogdanovich also describes him as a man with zero boundaries who was a pimp in all but name. He describes meeting a 19-year-old woman he calls Tammy at the mansion. After acting as her saviour of sorts and trying to get her out of the party, Hefner and “several angry-looking buddies” tailed them and made Tammy go back to the party because she was Hefner’s “date” for the evening. According to Bogdanovich, Tammy later became a “high-priced call girl in Paris. None of the other Playboy girls I would come to know ended up much better.”

Bogdanovich first met Stratten while visiting the infamous Playboy mansion. He was in the middle of a career slump. After exploding onto the scene with his second film, The Last Picture Show, he made two more bona fide hits, What’s Up, Doc? and Paper Moon. He was also a celebrity director, someone who appeared in the tabloids frequently, largely because of his relationship with Cybill Shepherd. They had met while making The Last Picture Show and soon began an affair, even though he was married to his collaborator Polly Platt (for more information of her fascinating story, check out the You Must Remember This season dedicated to her.) After they made a couple of flops together, the press turned on them. Bogdanovich says in The Killing of the Unicorn that the pair of them were forced apart because the industry didn’t want them to keep working together. Shepherd quickly married and had a child after their split and Bogdanovich, by his own admission, fell into “more than a year of devastating promiscuity, which left me exhausted and miserable, hoping for an enduring bond that would never lose its strength or magic.”

It’s also worth noting that the reason Bogdanovich fell into a friendly acquaintance with Hefner was that Playboy had published nude stills of Shepherd from The Last Picture Show in the magazine, and in the settlement they came to over this invasion of privacy and consent, Hefner gave the pair the film rights to a novel he owned, Saint Jack. Bogdanovich asserts himself as being not like the other guys in his regular visits to the mansion after this, as though he was the only one who knew what was truly up in the grotto, but I suppose hindsight is 20/20 for him. Still, it adds this kind of scolding tone to very serious topics, emphasizing Bogdanovich’s cultural and moral savvy over a tougher reflection of his own culpability in systemic misogyny.

(Image via J. Kevin Fitzsimons. Copyright: 2010 The Ohio State University. Creative commons licence.)

He does paint a bleak portrait not only of Playboy, a place where women just lie there and take it, as one visitor describes, but of how miserable it made Stratten to be a part of this business. She didn’t like taking her clothes off or posing for photographs. She didn’t like her hair being bleached into the white-blonde shade that is synonymous with Playboy models of the era. During her Playmate of the Month photoshoot, she got through the embarrassment by thinking about how much she hated the entire enterprise until the hate created a kind of protective shield around her. After that issue was released, a later one showed Dorothy in a more lewd position. She hadn’t known that the photographer was still taking shots at that moment.

The Killing of the Unicorn also alleges that Hefner raped Stratten. Snider had apparently told Dorothy she could sleep with Hefner if it would benefit her career, which repulsed her. While staying at the mansion, one of Hefner’s secretaries allegedly called her at 1:30 am to tell her that Hefner wanted her to join him “for a little swim in the jacuzzi.” Afraid to say no lest it hurt her career (and her Visa was tied up in being an employee of Playboy), she joined him. Discourse around sexual assault at this time was limited in how it viewed what was and wasn’t consensual. In 1982, Ms. Magazine would write about “forced seductions” and “of the women’s problems in dealing not only with the often violent scenes, but with the guilt and complicity involved in the aftermath.” For a 19-year-old immigrant whose employment and residential status were directly linked to Hefner’s employment of her, it’s hard to imagine her ever being able to fully say “no” to a man who used women so frequently and flagrantly.

Hefner feels more present in The Killing of the Unicorn than Paul Snider, the actual killer, although he’s not sparing in his hatred of the murderer. A small-time and mostly inept crook with a string of failed enterprises to his name, Snider was the kind of personality who everyone wanted to get away from. He was the epitome of the toxic creep who emanated bad vibes (this is one thing that Eric Roberts absolutely nails in Star 80.) That seemed to be his biggest problem in succeeding in a world designed to accommodate misogyny: you still need at least a modicum of charm to make it work. Hefner kept Snider out of the mansion because, even by his lack of standards, the vibes were off.

That doesn’t make Snider any less sociopathic, as history would later show. He still looked for other girls to pimp out, and he lived off the money Stratten made. He even used her own earnings to pay for the private detectives he hired to tail her during her affair with Bogdanovich. When that romance was revealed, he tried to clear out her bank account by getting a random blonde woman to pretend to be her.

Bogdanovich wonders if Stratten ever really loved Snider. When asked why she married him in the first place, she says, “I didn’t want to get into an argument,” which might be the saddest reason ever to have a wedding. Bogdanovich theorizes that she first became attached to the older man because she was hurting after a messy break-up and Snider gave her her first real orgasm (Jesus, Peter.)

It’s clear that Bogdanovich was enamoured with Stratten. He talks glowingly of their brief ten months together in ways that are frequently sweet. A lot of it, however, is also pure objectification. He seems amazed that she liked to write poetry and that she would read the books he recommended to her, as though it was inconceivable for a barely adult nude model to enjoy literature. He rewrites They All Laughed to focus more on Stratten’s character, and has John Ritter, who plays her love interest, dress like him, oversized glasses and all. There are scenes directly inspired by his courtship of Dorothy, such as one where he reads her palm. She’s also unhappily married to a douchebag and falling for the older man who stumbled into her life. One more than one occasion, Bogdanovich describes their “lovemaking”, and I wondered why this wasn’t considered an invasion of her privacy on his part. Because he loved her? That doesn’t seem like a good enough answer. He doesn’t go so far as to sell himself as her saviour but he’s also so glistening in his sensitivity and maturity that he becomes The Only Good Man. Misogyny is a rot but he’s untouched.

(Dorothy and John Ritter in They All Laughed.)

Stratten’s brutal murder is described in blunt terms. It’s how the book opens. I think Bogdanovich was aiming for something clinically descriptive, like a crime scene report. But it’s tough to detail a woman’s rape, murder, and post-mortem sodomy without feeding into some of the lurid fetishizing of her death. He wants people to know what happened to Dorothy, something he’ll never be able to forget himself. That doesn’t make it any easier to read. It’s the backbone of the true-crime industrial complex: letting people revel in the worst recesses of humanity while allowing them to view it as an act of kindness or objective interest.

In the aftermath of Stratten’s death, the murder business boom was unavoidable. There were the films, the articles, and the Playboy tributes, which didn’t show Stratten nude at first but ensured her body would remain on display for masturbatory purposes in the following months.

The Killing of the Unicorn was, unsurprisingly, controversial. Reviews were largely negative, either unsettled by Bogdanovich’s naked grief and bitterness or concerned for his wellbeing. People called it a "sometimes provocative but relentlessly self-serving version of Stratten's life and death." The Chicago Tribune called it "a shabby little shocker." The general tone of the criticism was, "Dude, should you have even published this?" It's hard to disagree with that.

Private eye Marc Goldstein later sued Bogdanovich for $10 million for being libelled in the book after Bogdanovich claimed that he aided and abetted Snider in the murder. That, combined with the exorbitant costs of trying to release They All Laughed independently, led Bogdanovich to file for bankruptcy. While he made some commercial hits after this, most notably Mask starring Cher, his career never recovered.

Hefner suffered a stroke in 1985 and blamed the stress of Bogdanovich's allegations for it. He also hosted a press conference to accuse Bogdanovich of statutory rape of Dorothy's younger sister Louise. The Stratten’s former stepfather Burl Eldridge was brought forward as a witness to claim that Bogdanovich had slept with Louise when she was a teenager and that he'd paid to have a plastic surgeon make her look more like Dorothy. Louise and her mother sued but eventually dropped the case because of the costs. In 1988, Bogdanovich married Louise Stratten. They were together until 2001 and remained collaborators until his death in 2022.

Louise Stratten spent many decades working with Bogdanovich and also speaking out in support of women like her sister who were abused by their spouses. They seem to have been very happy together, even after they divorced, but marrying the younger sister of your murdered girlfriend was never going to be anything other than extremely weird for Bogdanovich.

A 1989 article from People described how some thought he was "too close" to the teenage Louise, sending her to a private school and buying her expensive gifts. Stratten's mother Nelly said, "I feel he wants her because of a guilt trip. This happened to my other daughter, who got her head shot off, and it’s gonna happen to this one. He didn’t do it, but he was involved. If he is in love with one daughter, how can he be in love with the other daughter?” A fair question for any mother to ask. Everyone quoted here seems pretty blunt in their assertions that Bogdanovich wanted a replacement for Dorothy, and who better than her sister? Said one relative of Louise, "Peter was so in love with Dorothy that the only person he really even associated with was that little baby sister. He has never been able to let go of the feeling. Perhaps he’s trying to capture what he had with her.”

Playboy is still around, although its cultural footprint is far smaller in the age of digital porn, #MeToo, and women prioritizing their own pleasure. They took the nudes out for a while but put them back in. Hefner died in 2017 at the age of 91. He is interred at Westwood Memorial Park in Los Angeles, in the crypt beside Marilyn Monroe, for which he paid $75,000 in 1992. Another instance of that man trying to violate that woman without her consent. He died with his reputation largely intact but it's since crumbled to dust.

Former girlfriends like Holly Madison and his widow Crystal detailed the hostile environment Hefner created at the magazine and mansion, encouraging competition and body-shaming among the many women who lived there as his "girlfriends." The A&E documentary series Secrets of Playboy made damning claims of drug use, sexual assault, blackmail, and statutory rape by Hefner and his goons. The PLBY group, now publicly owned, distanced itself from Hefner in a statement released shortly before the first episode was released. They said, "Today's Playboy is not Hugh Hefner's Playboy. We trust and validate these women and their stories and we strongly support those individuals who have come forward to share their experiences."

A lot of this stuff was known during Hefner’s lifetime, but he fostered an image as a cuddly lothario who was wholesome in his “love” of women and sexual liberation. E! had an entire reality TV series, The Girls Next Door, dedicated to fostering this fantasy. There’s still this prevailing idea that Playboy was “classy” and so much more acceptable than the tawdry lad’s mags of the ‘90s or the current era of OnlyFans (because sex workers seizing the means of production is bad for pimps.)

(Holly Madison in A&E’s Secrets of Playboy.)

As I get older, I realize how stories like Stratten’s murder are not special, per se. Tales of grizzly celebrity crime are positioned as somehow different from the kind of trauma the rest of us plebs suffer with, and certainly, the seedy power structures of the entertainment world do breed a kind of corruption and cruelty that is especially potent. But ultimately, Stratten’s case is so unbearably sad because there is nothing less special than a woman being murdered by her spouse. Men are the biggest risk in women’s lives, more than being hit by cars or succumbing to illness. It’s depressingly common to read of stories like Stratten’s, where the men they were supposed to trust brutalize them in life and death. Guns are usually involved. The authorities either don’t care or don’t do anything until it’s too late. The details of Stratten’s death are obviously abhorrent and stomach-churning, but they’re also too familiar. These stories are in the newspapers every day. Right now in France, a woman is bearing witness to a trial against her husband and dozens of men who raped her. This is life as a woman, the perennial threat hovering overhead. This is not the fear of the unicorn, a unique phenomenon experienced by a sole victim.

Reading The Killing of the Unicorn was an odd experience. Bogdanovich’s grief is undeniable. A lot of the book feels like his mourning diary or a therapy session that never should have seen the light of day. He had to live with the weight of what happened to Stratten, and watch how her legacy was reduced to something so tawdry. It never stopped being so either. Many parts of The Killing of the Unicorn are deeply affecting, and it does succeed in showing Stratten as more than what she was sold as to the world (although the bar was low on that front.) Still, I’m inclined to agree with People’s review because it was tough to escape the sensation that Bogdanovich was fetishizing Stratten as much as everyone he condemned. After the second or third description of their love-making, I had to wonder what his point was. It certainly didn’t seem to be one that prioritized Stratten’s legacy over Bogdanovich’s. When he describes the Star 80 reviews and compares them to the reviews for They All Laughed, gleefully noting that one critic who hated the former loved the latter, Stratten’s memory seems to come second to his genius.

I really dislike how that Pulitzer Prize-winning Village Voice article treated Stratten as a passive figure in her own life and death, but it did nail how all the men in her life failed her, including Bogdanovich. He was not immune to the ogling fetishism of youth and beauty, and while he clearly loved Dorothy Stratten, he still seemed to view her as an accessory to his own creative prowess. I’m grateful for him giving a richer, more empathetic portrait of Stratten herself. She seemed like a sweet young woman who loved her family, her poetry, and was still trying to figure out who she was. But you don’t necessarily finish The Killing of the Unicorn with a greater sense of her as a person independent of the men in her life and the tragedy that befell her. She will always be tied to three men: Paul Snider, Peter Bogdanovich, and Hugh Hefner.

Roger Ebert said that while he understood why the book was written, he wished Bogdanovich hadn’t published it. I agree, but here it is. And here’s the true crime market that continues to appropriate Dorothy Stratten. I fear Ryan Murphy or Netflix getting their grubby mitts on this story. Some things should just be left to rest.

Thanks for reading. This issue was free for all because I won’t be able to get a new issue of the Gossip Reading Club live for a bit due to post-TIFF rearranging and work commitments. Please let me know if there are any other stories or topics you’d like to see discussed on this newsletter. All recommendations are greatly appreciated.

Painful to absorb the reality of the dark side of human nature. The idea that Dorothy was complicit in her own demise is not a popular notion, but would be wise for all to take note. It sounds a lot like "blaming the victim", but we all have and make choices, and sadly her choices contributed to this awful outcome. Choose wisely who you associate with as this influences outcomes significantly. I think of OJ and Nicole Brown Simpson as I write this. Stay safe my friends.

Very well written and brilliantly empathetic